Since 2021, Afghanistan has faced an acute fiscal shock following the near‑collapse of external financing. Prior to the Taliban takeover, international aid financed more than two-thirds of public spending and around 40 percent of GDP. Its sudden withdrawal created a revenue vacuum that could not be filled through domestic taxation in an economy marked by contraction, informality, and mass poverty. In this context, mining has re-emerged as a central fiscal strategy, framed as a path toward self-reliance and revenue generation

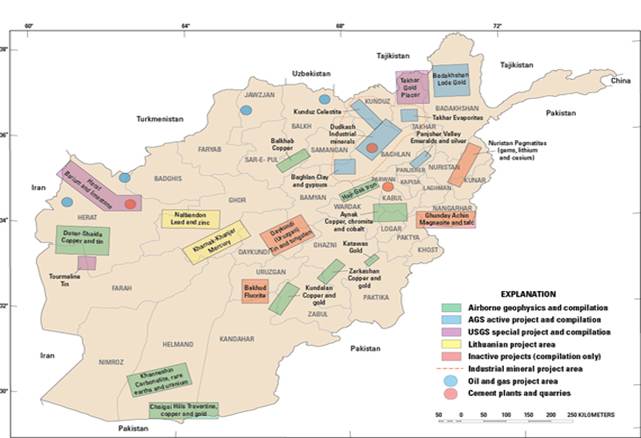

The logic is straightforward; Afghanistan possesses significant untapped mineral deposits, often cited as being worth up to USD 1 trillion and extraction can generate cash relatively quickly. For a regime that lacks international legitimacy and faces sanctions, limited access to the global financial system, and shrinking economic activity, mining represents one of the few remaining sources of fiscal liquidity. While concerns over corruption, rent capture, and misuse of mining revenues are substantial, even under the most optimistic assumptions, reliance on extractive revenues carries serious macro-fiscal risks that extend beyond governance failures at the sectoral level.

Institutional risk and Resource curse

The first and most fundamental risk is that mining revenues are increasingly used as a substitute for taxation, rather than as a complement to it. A large body of political economy literature shows that taxation is not merely a revenue tool but a key driver of state capacity and accountability. It’s is widely believed that governments dependent on non-tax revenues face weaker incentives to build accountable institutions and growth-oriented policies.

Afghanistan already experienced this dynamic during the aid-dependent period before 2021, when domestic revenue mobilization remained structurally low despite two decades of international engagement. Mining now risks replacing aid with another form of unearned income, leaving the fiscal structure detached from domestic production and household livelihoods. This creates a state that can finance basic operations without investing in the conditions needed for growth, while postponing the politically difficult task of building a broad tax base in agriculture, services, and small enterprises.

Fiscal Risks of Mining-Led Revenue Dependence

A second risk lies in the quality and stability of mining revenues themselves. Extractive revenues are inherently volatile, highly sensitive to global commodity price fluctuations, and typically concentrated in a small number of sites and actors. IMF analysis of resource‑dependent low‑income countries shows that such dependence is associated with significantly higher revenue volatility and weaker expenditure planning. Moreover, mining is capital‑intensive and generates limited employment. In Africa, for example, extractive industries contribute substantially to government revenues, export earnings, and economic growth, yet they employ less than 1 percent of the workforce. When these revenues become central to fiscal planning, they encourage short‑termism, prioritizing immediate extraction to meet near‑term budget needs rather than investing in long‑term productivity.

This dynamic often distorts expenditure priorities. Instead of financing sectors with high employment and growth multipliers such as infrastructure, human capital formation, or agricultural productivity, resource revenues tend to be absorbed by recurrent spending, security, administrative expansion, patronage networks, and in Afghanistan’s case, ideological priorities. Over time, this weakens productive capacity and increases vulnerability to future economic and fiscal shocks.

Policy Implications: Constraining the Damage

If mining is to play any role in Afghanistan’s fiscal framework, it must be treated as a constrained and secondary source of revenue not as the backbone of the economic strategy.

First, mining revenues should not be used to finance routine recurrent expenditures. Instead, resource revenues should be explicitly linked to productivity‑enhancing investments, particularly in agriculture and basic infrastructure, where returns in terms of growth and employment are highest. International experience suggests that channeling resource income toward such investments improves long‑term growth outcomes and reduces the risk of fiscal dependence.

Second, any expansion of extractive activity must be accompanied by deliberate efforts to improve livelihoods and broaden the tax base, even if only at modest scale. Supporting agricultural incomes, small enterprises, and market integration is essential not only for inclusive growth, but also for rebuilding the fiscal link between the state and the broader economy. Without this link, mining revenues risk further weakening incentives for domestic revenue mobilization.

Third, a portion of mining revenues should be saved or stabilized through simple fiscal rules to reduce volatility and limit politically driven spending cycles. Even in low‑capacity settings, basic revenue‑smoothing mechanisms such as stabilization funds or conservative budget‑benchmarking rules can help mitigate the fiscal risks associated with commodity price fluctuations.

In sum, mining may help the Taliban survive fiscally in the short term, but survival should not be mistaken for development of the country. Without clear constraints and a broader macro‑fiscal strategy, reliance on extractive revenues risks deepening a resource curse defined not by excessive wealth, but by prolonged economic stagnation and delayed reform.