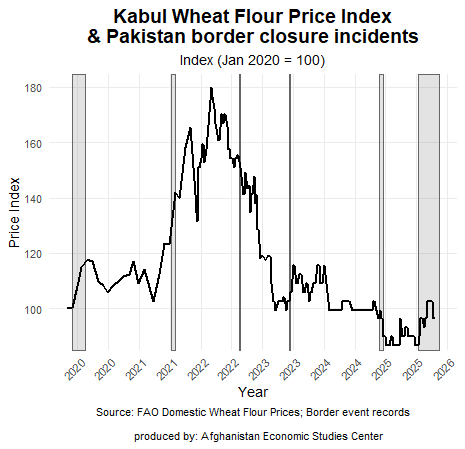

Recent border closures between Afghanistan and Pakistan have again triggered sharp increases in the prices of wheat flour, rice, vegetables, and other essentials across Afghan markets. During the late‑2025 shutdown that is one of the longest in recent decades, food prices climbed steadily as cross‑border trade has been disrupted for more than 70 days now. The Taliban‑run National Statistics and Information Authority (NSIA) reported that monthly food prices in Kabul rose by 4.2%, in December 2026 with grain prices up 3.5%, cooking oil 13.9% and vegetables 29% during the first 2 months of the prolonged closure period. This trend contributed to a rise in general inflation in the country as the point-to-point inflation (December 2025 against December 2024) was 9.6 percent.

The economic consequences of these disruptions were amplified by the scale and duration of the closures. Earlier border shutdowns during the COVID‑19 period similarly produced rapid increases in wheat flour and cooking oil prices, demonstrating how sensitive Afghan markets are to interruptions in cross‑border supply chains.

Retail wheat flour prices in Kabul rose sharply during the early COVID-19 border disruptions in 2020, when key crossings at Torkham and Chaman/Spin Boldak were temporarily closed. A more pronounced spike followed in 2021–2022 amid political tensions and renewed border restrictions, compounded by global commodity pressures. The pattern highlights Afghanistan’s vulnerability to cross-border supply shocks and limited domestic buffers.

Trade disruptions and structural food insecurity

These are not isolated disturbances but symptoms of deep structural vulnerability. Afghanistan relies heavily on imported wheat and wheat flour, rice and cooking oil and lacks both the market depth and logistical resilience to withstand disruptions. When borders close, even temporarily, the consequences reverberate across a population already struggling under deteriorating economic conditions. 17.4 million Afghans now face high levels of acute food insecurity (IPC Phase 3 or above), one of the world’s largest food crises. Humanitarian funding that was once the lifeline supporting food and cash assistance, has shrunk dramatically. The 2025–2026 hunger crisis has intensified as aid flows declined from billions of dollars annually to a fraction of previous levels. Compounding this pressure, food demand has surged as 5.4 million returnees have re‑entered the country from Iran, Pakistan, and elsewhere, further straining already fragile markets and deepening the gap between supply and need.

Border closures, therefore, hit Afghanistan at its weakest point. They magnify scarcity, inflate prices, erode purchasing power, and deepen deprivation for families already forced to choose between food, fuel, and medical care. They also interrupt the flow of humanitarian supplies that cross through Pakistan, creating secondary impacts on aid delivery and market functionality.

Building resilience in a crisis‑driven food system

Given these realities, establishing a national grain reserve emerges as a practical and urgently needed policy tool. Many countries with comparable vulnerabilities such as limited domestic agricultural output, high exposure to climate and political shocks, and dependence on imports operate strategic food reserves. For instance, Ethiopia’s emergency grain stocks allow rapid response to drought-induced shortages, while India’s buffer stock operations stabilize cereal prices during production shortfalls or supply chain disruptions. These examples demonstrate how reserves can cushion the impact of external shocks, especially for essential commodities like wheat flour whose availability directly affects household survival.

For Afghanistan, a grain reserve would provide several critical benefits. First, it would serve as a shock absorber, allowing the government or in the current context, humanitarian partners coordinating with de facto authorities to release grain during emergencies such as border closures, droughts, or winter bottlenecks. This would reduce price volatility, preventing sudden spikes that push households deeper into crisis. The signaling effect is also important: knowing there is a reserve discourages speculative hoarding and exploitative pricing, which often intensify shortages during border disruptions. Second, a reserve would protect household welfare at a moment when incomes are falling and assistance is shrinking. With food accounting for the majority of household expenditure and real wages stagnant, stabilizing staple prices is one of the most effective ways to prevent deterioration in nutrition and well‑being. Third, a reserve would strengthen Afghanistan’s humanitarian infrastructure, providing a domestic buffer that complements international assistance and fills gaps when aid pipelines are disrupted or underfunded.

Moreover, in a country where 80% of the population depends on agriculture for livelihood, a reserve can be integrated with broader development policy. When procured during periods of surplus production, it can support farmers by guaranteeing demand; when released during shortages, it protects consumers. This dual role aligns with long‑term goals of stabilizing rural incomes, reducing dependency on imports, and improving food system resilience.

Establishing such a reserve can also be challenging as governance capacity, financing constraints, and risks of market distortion are real but manageable. Transparent procurement rules, modest initial stock levels, periodic rotation to maintain quality, and coordination with humanitarian agencies can significantly reduce risks. Importantly, the reserve should be framed not as a permanent subsidy or price control mechanism, but as a targeted stabilization tool activated only during genuine supply shocks.

In sum, Afghanistan’s recurring food price crises which are intensified by regional political tensions, sharp reductions in humanitarian aid, climate‑related shocks, and deepening poverty under Taliban governance, underscore the urgent need for institutional mechanisms capable of absorbing predictable disruptions. These pressures have repeatedly exposed the fragility of an import‑dependent food system and the absence of reliable buffers when borders close or supply chains falter. A national grain reserve offers a pragmatic and evidence‑based response: a targeted tool that can stabilize markets during sudden shocks, protect households from devastating price spikes, and reduce both the human and economic toll of future crises. By creating even a modest but well‑managed reserve, Afghanistan would take an important step toward strengthening national resilience and shielding millions of Afghans from the next border standoff, climate emergency, or global supply interruption.